Len McCluskey fantasises about adopting Crassus’ approach for the fate of the Blairites in the post-Miliband Labour party.

Len McCluskey fantasises about adopting Crassus’ approach for the fate of the Blairites in the post-Miliband Labour party.

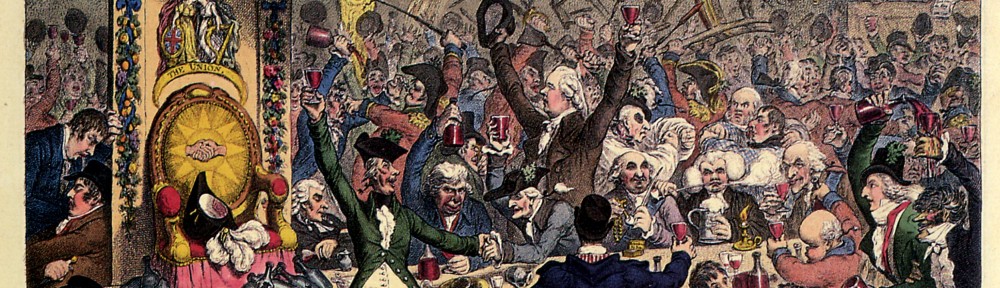

The old staple of ‘bread and circuses’ used by ancient Roman politicians to appease the their electorate is back with a vengeance when it comes to the current crop of post-election leadership competitions. Much like the Roman arena, the braying mob (such as myself) have the opportunity to see the dramatic beginning and ending of political careers amongst the competitive combat of the gladiatorial arena. In that respect we’ve currently got an embarassment of riches in the UK, with the Lib Dems, UKIP, and Labour all engaging in the predictable yet satisfying outbursts of blood-letting as candidates jockey for position after the failed leaders of the 2015 general election fell on their swords.

While UKIP provide the stage for the continuing soap opera that is the resurrection/defenestration of Nigel Farage’s leadership career, the Lib Dems have settled for a lacklustre evaluative analysis of relative mediocrities. In a rare instance of UKIP-Lib Dem empathy, both parties lack alternative candidates with any obvious gravity, and both suffer from the relative boost these post-defeat leadership contests provide to the swivel-eyed loons amongst the party membership. Labour, by contrast, have decided to provide their swivel-eyed loons with not one but two platforms for the inevitable post-defeat internecine warfare. Both of which offer the now-traditional choice between Blairite reform or retreat into the comfort zone of the loons where the ideological purity of the party can be untroubled by inconvenient electoral success.

First up is the UK leadership contest, where Ed Miliband’s departure has predictably failed to provoke the soul-searching inquiries necessary to change electoral strategy. The party’s continuing rejection of Blairism – or more specifically, an updated attempt to discover a policy platform which might actually make them electable – is reflected in the overall lack of Blairite candidates and the obligatory rejection of Blairism. This was particularly notable with the current front-runner Andy Burnham, hastily distancing himself from his prior career as a government minister tainted by Blairism. The shortage of Blairite contenders was brought into sharp relief by the comic value of Chuka Umunna’s brief campaign, which was so dynamic that (to resurrect an old Ciceronian joke about a place-holding Roman consul) the prospective leader almost didn’t get any sleep during his candidature.

In the interests of maintaining my criticism of Ed Miliband in every possible context, I can’t leave Umunna’s candidature without commenting on the opening sentence of his withdrawal statement.

‘Shortly before the election campaign, I made the decision, in the event that Labour was defeated and a new leader was to be elected, to stand for the leadership of the party….’

Clearly Ed’s defeat was completely unanticipated.

Meanwhile, without being too critical of Umunna, it is clear that his candidature was, in the final analysis, not serious; at least to the extent of his willingness to endure the predictable level of press scrutiny which would follow. So much for the great hope of the Blairites. To pick up on one of Umunna’s points in the video originally declaring his candidacy, this is why the reconstruction of the Labour party will take more than five years, possibly more than ten. Another defeat is necessary before the party will be willing to learn the lesson, and accept the necessity of ‘Blairism’.

The necessity for learning the New Labour/Blairite lesson all over again is handily demonstrated in the Labour leadership north of the border, where Jim Murphy resigned despite winning a vote of confidence on the party’s executive 17-14. I have some time for Murphy, largely on the obvious grounds of his performance for the ‘No’ campaign in the Scottish referendum last year. In contrast to the craven incompetence displayed by many of his Labour colleagues, Murphy at least demonstrated clear moral courage by his personal campaigning, and in my view did much to expose the underlying reality of anti-democratic intimidation amongst many in the ‘Yes’ campaign. However, Murphy is a prisoner of the party context, which means that he lacks the power base necessary to effectively lead the party, as the narrow vote on the executive in his favour indicates. Ultimately, this is why Scottish Labour need a different leader, but that need is driven by internal political dynamics of appeasing the loons desperate to recapture the ‘progressive’ constituency lost to the SNP rather than a realistic search for a programme with broader and more genuine national appeal.

Just in case a further confirmation of the determining nature of that internal conflict was required, Murphy provided it himself when he claimed he would produce a report advocating reform of the voting structure inside Scottish Labour away from the current situation where trade unions, parliamentarians and party members constitute a third of the electorate respectively. The rationale for this has been the conflict between Murphy and union leadership in the person of the Unite leader, Len McCluskey. As Murphy puts it;

‘Sometimes people see it as a badge of honour to have Mr McCluskey’s support. I kind of see it as a kiss of death to be supported by that type of politics.’

The problem becomes evident when McCluskey’s attitudes are explored. A hard-left one-time supporter of Liverpool’s Militant Tendency in their glory days, McCluskey weighed in with vocal support for local Unite official Stevie Deans when Deans was accused of stacking local Labour party membership to ensure the selection of his favoured candidate for the Falkirk by election in 2012. The scandal emerged in 2013 when local people complained that they had been recruited into the party without their permission, triggering a suspension of the candidate selection procedure and a police investigation. Both investigations blew over, with the police notably concluding that no criminal activity had taken place, although this was alleged to be a result of evidence being withdrawn by witnesses.

The most important outcome from this was the catalyst it provided for Ed Miliband’s brief challenge to McCluskey’s behaviour and the intense but temporary attention it focused on Miliband’s proposals for reforming financial contributions of political parties. While the latter was aborted largely because of conservative opposition to limiting the contributions of individuals for obvious reasons of Tory self-interest, the fact that it arose at all was because of the evident conflict of interests in the Labour party. That conflict arose between traditional picture of apparently corrupt McCluskeyite/Deanite union machine politics and a belated attempt by Miliband to recapture some measure of Blairite distance from such behaviour. Of course, the reality was that Blair’s attempt to distance Labour from such traditional behaviour drove the party into the Ecclestone/Levy scandals over contributions as an alternative to such problematic union funding.

The original problem endures, however, with a particular Scottish resonance for Labour’s search for a new strategy after another electoral failure. McCluskey’s intervention to threaten disaffiliation of Unite political funding from Labour came in the same breath as an implict warning that Unite in Scotland might find a more congenial relationship by funding the SNP. I think we can safely accept his subsequent furious backpeddling as confirmation that his original intervention was a fairly crude attempt to warn off any return to Blairite heresy by playing on SNP electoral success at Labour expense.

The failure to resolve the union funding issue by Ed Miliband, despite his reform of leadership elections, and by Labour generally means that it remains an ulcer to be expolited by union leaders like McCluskey, somebody with prior form for threatening to rethink his union contributions to the party if it elects a new leader insufficiently left-wing for his tastes. That sort of retro seventies union strong-arming takes us right back to the pre-Thatcher era, at the direct expense of Labour’s credibility with the broad mass of the British electorate. But we already know their perceptions are an irrelevance to the dominant constituencies in Labour, so McCluskey’s gambit will probably be successful in setting the tacit boundaries of the Labour leadership contest.

In the larger sense this means the dynamics of the Labour leadership contest are less about the gladiatorial success or failures of the leadership candidates fighting and falling in the arena to the amusement of the electorate, and more about the powerful political figures funding the games. In the late Roman Republic of Cicero and Caesar, the obvious candidate for this role would be Marcus Licinius Crassus and his employment of his massive personal wealth to buy elections and influence for client politicians fighting their way up the greasy pole of Roman electoral politics.

Crassus eventually met an ignominious end outside the arena of Roman internal politics in a disastrous military expedition against the Parthian empire, a risk McCluskey will always be able to evade while union and Labour politics remain insulated from such inconvenient collisions with external reality. As Ed Miliband has found out, however, such immunity does not extend to those products of the system who have to submit themselves to the verdict of external reality in the form of public elections. So for the encouragement of the next Labour leader: Forward to Oblivion!

So Herr Vigg you hav your own blog!